If you have been following this blog, you have watched the development of a zinc plate though polishing, beveling, line drawing etch, tonal or aquatint etch, spit bite aquatint, and using paint markers and grease pencils as acid resist.

You have seen a number of proofs of the image along the way, called “Stage Proofs” – proving the plate at different stages of development.

The final stage of development is working out the color wipe. The plate could be printed with black ink only, resulting in shades of grey, or inked in all one color, such as sienna, for a monochromatic image of shades of that color.

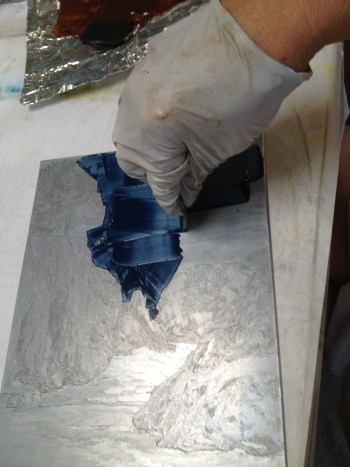

I print in a technique called “a la poupee” – a French term literally translating as “by the dolly”. It means dabbing and wiping different colors on different parts of the plate.

Many of my etchings are done this way, where colors are applied to sections of the plate and wiped separately, then the all of the colors printed at once on the etching press.

It is possible to wipe a base color and then apply another color over the top of it for a blended effect, and to bring color from one area of the image into another area. I do a combination of these for most of my color wipes.

On MacKerricher Beach, I started with two blues, one that was mostly Payne’s grey for the cloudy sky, and another for the waves coming through the gap. The rocks and cliffs were all wiped with sienna, and the trees and bushes with Cascade Green. The resulting print was nice but didn’t quite “pop” for me, so I remixed the colors a little, but more importantly, added a fifth color, a darker brown.

This color combination is satisfying, and the placement of the layered green and brown is just what I was looking for. Now the challenge will be to make the overwipe layer areas similar from one print to the next.

Great attention to detail will be necessary to match the bon a tirer with subsequent wipes. While I don’t expect them to be identical, it will be possible to wipe too much – leaving the image t0o pale – or to dab the colors onto a larger or smaller area, creating a different look which may not be as satisfying. These prints are usually destroyed, although if it is interesting in it’s own right, just different from the edition, it may survive as an “artists proof”.