Printing Limited Editions

One of the wonderful attributes of original printmaking is that, once you have created the plate, you can choose how many times to print it. More than one person can acquire your original work because each impression pulled from the plate is an original print. There are a variety of factors that influence the number in a limited edition of original hand-pulled prints.

Deciding on edition size

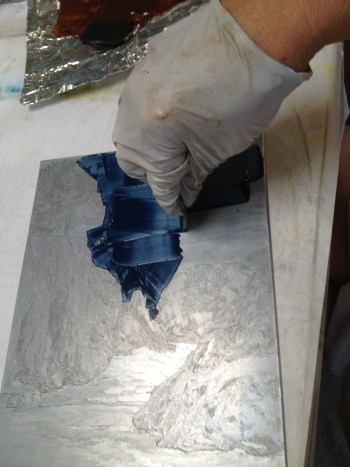

Most of my editions are around 25. This number was arrived at rather arbitrarily, thinking about the number of hours that go into developing a plate, and the relatively low price collectors will pay for a print as opposed to an oil painting, especially for a young artist just starting out. I toyed with an edition of 40 and a few editions of 16 or 20, before deciding that 25 seemed like a good number. Some plates have a naturally limited number. Drypoint on plexiglass, for example, only holds up for about 5 prints before it loses it’s special line qquality. Drypoint on zinc may hold up for 20 oe 25 before you can see the wear on the plate. Other plates, such as a zinc etching or a collagraph made from Masonite and acrylic medium, may physically hold up for considerably larger editions.

There may be market reasons to increase the size of the editions. There was a period of time during which my work was represented by a wholesaler to the design trade. Because of the investment they would make in marketing materials (this was before the internet and easy digital reproduction and distribution of marketing materials), they needed the editions to be no smaller than 100 and and requested even larger editions of 150 for some images.

I knew that technically this should be feasible – zinc plate should hold up for that many prints, I had been told, though I had not printed an edition that large. My collograph plates seemed likely to be even more durable, being well coated with acrylic medium as a final coat regardless of what materials went into creatin

g the plate. That sounded like a huge number to print, but they were willing to buy prints outright in lots of 10 or 20 at a time rather than take them on consignment, so I was willing to set larger editions for those works. You will find a few editions from that time period that number up to 150. Read more >